Source: American Rider –

Source: American Rider –

First thing you notice about the Steve Huntzinger shop in Arroyo Grande, California, is the length. It looks like an Old West bunkhouse/horse barn and runs 150 feet long.

“Well, that’s with the addition,” he admits. “I just ran out of room.” The extra 30 feet houses a few pending restoration projects, a small collection of quarter midgets and go-karts, his wife’s 1957 Ford Thunderbird, and his 1932 Ford sedan.

But behind the building’s rustic exterior is where the real magic happens, in a workshop more like an operating room than a biker garage. Talk about tidy. The place is so clean and well-lit, it’s almost unsettling. The proprietor of Quality Restorations can read my thoughts.

“Yeah,” he tells us, “I’m a neat freak.”

Steve Huntzinger, 75, is one of a handful of restoration experts whose exemplary work is in steady demand – a coveted status he has enjoyed for the past four decades. As a kid in Pasadena, California, he got the tinkering bug early on from his stepfather, who was into hot rods. Too tall for a minibike even as a pre-teen, Steve built a 20-inch bicycle with a Briggs & Stratton engine for himself. The athletic field at a nearby school proved to be a handy practice track.

“I could ride for 15 or 20 minutes before they’d chase me off,” he recalls. Before long, another youngster began to show up and watch from behind a fence. “So one day I went over and said, ‘Hey, you want to ride this thing?’” Dean Hensley hopped over the fence, and thus began a friendship that lasted for the next 30 years. “We went everywhere and did everything together. He was my best friend.”

Throughout high school, the two pals collaborated on motorcycle projects and went dirt-track and desert racing together. Then in 1968, at a TT race near Lake Elsinore, Dean crashed while leading and was hit by two following riders. The injuries left him paralyzed from the waist down.

“His mom hated me till the day she died,” Steve says, “because I got him into motorcycles.”

But being in a wheelchair didn’t diminish Hensley’s enthusiasm for motorcycles. He went on to study graphic design at Pasadena City College, and he built a successful sign business specializing in decorative antique-style mirrors and began investing in real estate. When Huntzinger finished his military service and found work as a mechanic at the local Honda shop in Pasadena, the childhood chums reconnected as motorcycle junkies.

What’s Old Is New Again

Sitting between a lathe and a parts shelf in Huntzinger’s tidy shop is an immaculate 1912 Harley Single.

“This is the first one I restored correctly,” Steve Huntzinger relates. “My first one, also a ’12 belt, is in the back. That one was given to a friend of mine when we were 13 years old. He called me up and said, ‘Hey, let’s see if we can make this thing run.’ We messed with it for an hour or so and got it to fire. We had no idea they wet-sumped from sittin’, so it’s bellowing smoke – going out of the garage, in the kitchen window. His mom comes out and chews our asses out, saying ‘If you ever start that thing up again, it’s going to the dump!’”

Steve says he and the friend joined the military years later, and a while after they got out, the friend said the bike was “all apart” and that he’d never restore it. “So I bought it from him. It was my first effort. I had it pinstriped by a guy named Shakey Jake, who was a prominent ’striper around Pasadena in the ’70s.”

At the time, a good source for early Harley parts was the legendary Bud Ekins, who was always happy to help the youngsters.

“He was a great man,” Steve says. “If I couldn’t find a part, he’d lend me one I could use for a pattern. ‘Just take one off McQueen’s bike,’ he’d say. ‘I know you’re good for it. And you’ll only fuck me once.’”

Researching the ’12 Harley led Steve to Lyle Parker’s shop, where he noticed the Burt Munro Indian streamliner in the back. Parker had bought it from the Sam Pierce estate and later sold it to Indian enthusiast Gordy Clark. Dean Hensley bought the Indian racer in 1986 and decided to restore it.

“Everybody laughed at him, said he was wasting his time,” Steve recalls, adding that Hensley sadly died in a freeway accident in 1992 at the age of 42. Looking back now, Huntzinger thinks it was a mistake to have restored the Indian from its former patina.

That brings up the complaint lodged against many restorers – that their work is “over-restored,” which has led today to the rising values of unrestored machines. “It’s only original once” is a common expression among collectors. When it comes to concours-level motorcycles, Steve thinks everything is over-restored.

“Take my ’32 Ford sedan for example,” he says. “You look down the drip rail and you can see where every spot weld was from the factory. But that’s not good enough if you’re going to enter it in a show – gotta make ’em disappear. In my opinion, that’s over-restored. But in the real world, it isn’t, because you’re doing it real authentic, and you’ve got to do it better than they did because you’re starting with shitty stuff.”

He says the same thing applies to bikes, that they never came out of the factory as pristine as they could be restored.

“They were real nice when they were new, but not as nice as we can do it. On the early stuff, they soldered the tanks together, filed it down, and painted it. Even the cars as late as the ’40s and ’50s, the hoods and doors didn’t line up. They were selling cars that were expected to last a few years, then everybody would buy another one.”

Four of the bikes in Steve’s shop belong to customers, while the other dozen or so are his own. In a perfect world, he says, he’d get paid for working on his own stuff, but he knows that won’t happen and enjoys the use of his own machines. The work for clients keeps them running.

Huntzinger says his 1937 Chief is “an absolute pleasure to ride.”

“I just put in one of those new 4-speed constant-mesh transmissions, and it’s kind of like cheating. You get going about 55 and click it into overdrive and just idle along. No more double-clutching or grinding; it’s like butter. I had a real nice ’46 Harley Knucklehead, but it had real clunky shifting. They say the Knuckleheads were much better with 18-inch wheels – this one had 16s – but I was done with it when I got the Indian.”

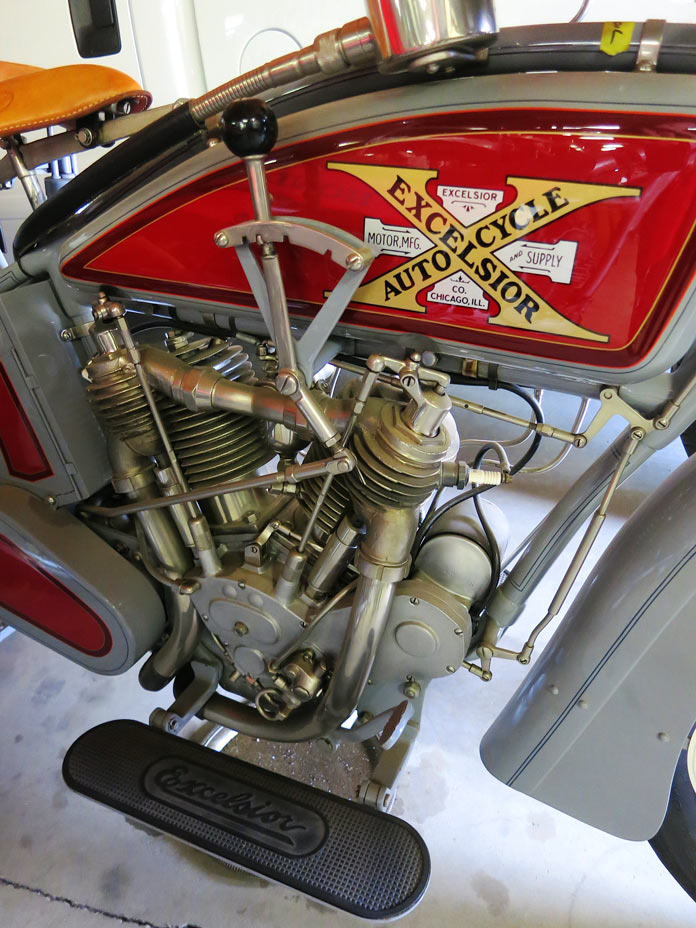

Indeed, Steve Huntzinger loves riding vintage bikes. He rode his 1915 Excelsior in the 2010 Motorcycle Cannonball cross-country ride just a few weeks after winning second-place in the Road Bike category at the prestigious Pebble Beach show.

“I was lucky at Pebble Beach. We won five out of the six trophies they gave that day. First place at Pebble was Mike Madden’s ’15 Henderson Four, and third was Brian Bossier’s ’36 Crocker. The Munro bike won the Competition award, and Dale Walksler’s 1909 Reading-Standard board-tracker was second in the Racing class. That was the best stuff that I ever had a chance to restore.”

Quality Restorations is Huntzinger’s business handle, and it’s not an empty boast, according to collector Clyde Crouch.

“He does his research and is good about sorting things out correctly,” Crouch says. “And he’s real anal about getting things right.”

“Quality” is a difficult word to define. Robert Pirsig spent a whole book, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, trying to do so. But you know it when you see it, and that’s certainly the case with the masterful restoration work of Steve Huntzinger.

Find more stories by T.J. Rafferty

The post Steve Huntzinger: Craftsman of the Classics appeared first on American Rider.